Do Angels Carry Our Prayers to God?

On the central themes of Yuzuru Hanyu’s RE_PRAY

For the sake of easier understanding, Yuzuru’s character Re_Pray is referred to as “Yuzuru.”

Unless otherwise cited, quotes are pulled from his self-written dialogue throughout the show on Day 1.

What is the function of a prayer? It can be grandly ceremonial or strictly personal. It can be an expression of gratitude, of supplication, of mourning. You can settle your sense of uncertain ease regarding the future by sending out a prayer. You can atone for your sins by praying for forgiveness. You can pray when you desperately want to feel less alone. In the broadest sense of the term, it is a way to communicate with a deified higher being, a call beyond the mortal everyday realm.

Whenever you want to speak to god, in whichever form it may take—you pray.

As Yuzuru makes his way through the combat-based in-game narrative of “RE_PRAY,” the endless violence and bloodshed bogs him down, but stopping is not an option for him. What should he do in this situation? Should he be praying for survival? Should he be praying for absolution? Is there even a god out there who will listen to him, or would it just be a waste of breath that gets carried away and drowned in the wind? A distraction from the immediacy of the struggle for survival?

When faith becomes complicated, when you no longer know what god to pray to or what outcome to pray for, sometimes the act of prayer itself is the only ritualistic comfort you can hope for. In that case, you can turn your prayer into an invocation of the angel that resides inside of you. You can pray to regain yourself.

Part 1: The Three Poisons, the Cycle of Death and Rebirth

In Part 1, Yuzuru is trapped by the narrative. In Buddhism, the three poisons (greed, hatred, ignorance, represented in Buddhist art by the rooster, the snake, and the pig) are what cause sentient beings to be trapped in Samsara, the endless cycle of life, death, and reincarnation—as opposed to achieving true nirvana and becoming one with the cosmic forces of the universe. Within the context of the combat-based gaming world that Yuzuru has found himself in, there is only one aim—to win. And there is no other way to achieve that than by progressing through the storyline, taking the lives of others to consolidate your own power and ensure your own survival via elimination. It’s a zero-sum game.

“There’s life around.

Every single life.

If I grab it, I seem to gain the strength to escape from this raging stream.

Do you want to take this life?

[YES]

I got a flowing life,

Harvested the life of a creature,

Devouring.”

After he embarks on this path, Yuzuru continuously picks [YES]. Even as he doubts his choices, he continues to move forward in a singular direction. In the linear progression of the narrative, that’s all he can do. Even if he wants to stop his suffering, he is hesitant to quit the game—as that will surely result in a dead end. With this in mind, Yuzuru can only continue to advance forwards. He hedges his efforts on one final charge against the final boss. It is in this final charge that Yuzuru hopes to finally win over the game and thus attain his freedom from it.

But Yuzuru cannot truly win, even if he beats the final boss. He cannot find true freedom on this path no matter what he does, because he doomed himself the moment he chose the path of the three poisons. He is doomed by the narrative, and the way it marches forwards with its own fixed impetus. None of the choices made on this path born from violence and greed will affect the end result in any way. And they don’t—he progresses through the game, defeating his adversaries but progressively losing his tether on humanity as he gains material, physical strength. By the time he reaches the end of Part 1, he’s “cleared” the game—and a victorious Yuzuru tries to save the data and honour his accomplishments. But the data file is corrupt. Error.

Part 2: The Search for Meaning

Throughout Part 1, Yuzuru is too preoccupied with combat and the desperate fight for survival to do any sort of spiritual reflection, let alone prayer. It’s not until Part 2—when he refuses to go down the path of violence and plunges into the cosmic void—that he gets the needed reprieve to genuinely contemplate life and purpose.

He had been doomed by the narrative that only promises violence, and after denying him liberation, it now exhumes and drags him back for round two. This time, however, he’s determined not to repeat the same pattern of bloodshed. When the dialogue pops up again, he resolutely chooses [NO] when prompted whether he wants to take a life. The refusal to engage effectively breaks him out of the narrative structure of the game altogether, opening an alternate pathway to freedom. This spiritual undertaking is explained through the following three programs and their corresponding themes:

I. Requiem, traditional prayer

II. Water, recovery of the self

III. Haru yo Koi, work as prayer

I. Requiem, traditional prayer

Requiem is one of Yuzuru’s programs that is so heavy with history and lore, both in the context of its creation and in Yuzuru’s personal experience with it. In every iteration of it, both in terms of its original association with grieving and honouring 3.11 and in the context of Yuzuru’s deeply personal performance at Boston Worlds when he thought it could be his last performance ever, it represents a heavy, reverent grief that’s bound in between the physical realms, so much so that it feels like the very weight of the sky is crashing in on you. It’s a remembrance for the departed, rife with loss.

Contextualizing the program in this way is another way of expressing his past and his history with this program—calling out for a god, reaching out with a hope and a wish. Hoping that they’re listening, even when you have no idea where they might be, what their function might be, and whether or not they even exist.

“‘Requiem of Heaven and Earth,’ the new exhibition program that started in Kanazawa the week before. Shock, anger at the heavens, hopelessness and helplessness fell upon him. Feelings that are rampaging in his heart to the point of insanity surged out from every part of his body as he skated.” (Oriyama Toshimi, translation by yuzusorbet, Tumblr, 2015)

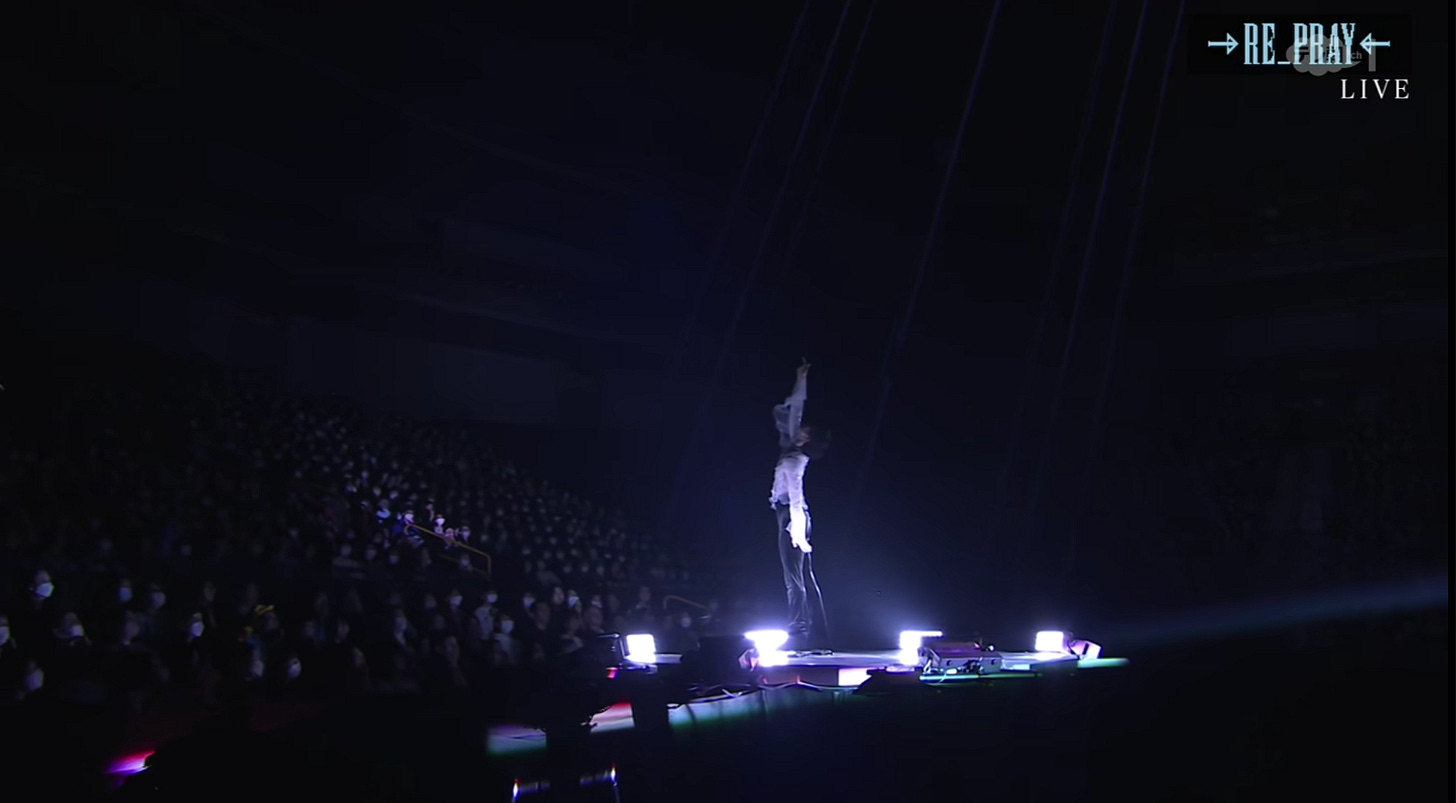

This is, however, the first time that we’re seeing him perform Requiem in front of an audience since that moment where he felt the most alone, and he’s now doing it on his own terms at a self-produced ice show as a pro athlete. In comparison to some other programs in the show, the lighting design for Requiem is relatively simple, with no patterns projected onto the ice and the backdrop fully dark except for the lanterns. Because it’s so stripped back compared to some of the more elaborate in-game worldbuilding we’ve previously experienced in Part 1, what’s extra striking is the uncomplicated warm colour of the singular spotlight that beams down on him, complemented by the floating lanterns—which are real and physically present within the arena.

It’s a wholly different Requiem this time. Instead of a repose of the dead, it’s a prayer of the living. After choosing not to take the life at the beginning of Part 2, he preserves that light within him, which becomes the source of glowing light that reflects back on him through the spotlight and the blinking lanterns. This time, there’s a warm hope in the sincere uttering of a traditional prayer that releases his wishes into the world the way the lanterns are released into the night sky. Beseeching a higher power to listen to him in spite of his history with the program, in spite of his weariness from doing everything right and defeating everything in Part 1 and still only being reckoned with an acute sense of loss and failure.

“Is it a god who made this game?

Is it also a god who is moving me?

Then, shall I call out?

Hey, god, you’re listening right?”

He releases his prayer into the night sky. He has hope at first, but right before the final note is struck, the lights are depleted of all warmth and colour and life as they turn white—the colour of mourning. The lanterns also go simultaneously white before being fully extinguished, leaving him in the darkness.

This is Yuzuru at his most vulnerable, having laid himself completely bare in asking for someone to listen to him, but realizing in the cold white light that there is no one there. It seems like it might be hopeless—even after choosing life, he’s still all alone. If Requiem is a prayer, it’s one that continues to go unanswered by any god.

II. Water, recovery of the self

After laying himself bare and receiving no answer, Yuzuru is left in the cold light before being submerged back into the darkness. This time, he’s even more alone and afraid that he’ll be that way forever.

“So dark that even god can’t observe.

I can move ‘freely’ in the darkness.

It’s so dark I can’t even tell if you’re alive, but it’s ‘freedom.’

I can’t go anywhere.”

But it doesn’t stay that way for long.

“A drop of water. It’s cold, yet warm?

I am alive, I can feel.

The road lights up.

I can move forward…

In the direction that god leads, to where the water shines.”

Something as insignificant as a single drop of water is able to break him out of the paralyzing darkness. As the narration ends, the two narrow beams of light that had bound Yuzuru within the singular path toward Samsara appear again—but this time, they’re blue instead of red. This time, that “path” on the ice dissipates with the opening notes to “One Summer’s Day,” making way for the ripples that breaks through the still surface of the water. The sensation of the singular drop of water has illuminated a whole new path for him, one that promises life instead of heralding death.

Water represents many things. It’s the element that nourishes all forms of life, capable of cleansing and washing away all grime and sin. In Buddhism, it represents death—but recognizes that mortal death is not the end:

“When we look at the ocean, we see that each wave has a beginning and an end. A wave can be compared with other waves, and we can call it more or less beautiful, higher or lower, longer lasting or less long lasting. But if we look more deeply, we see that a wave is made of water. While living the life of a wave, it also lives the life of water. It would be sad if the wave did not know that it is water. It would think, ‘Someday, I will have to die. This period of time is my life span, and when I arrive at the shore, I will return to nonbeing.’ These notions will cause the wave fear and anguish. We have to help it remove the notions of self, person, living being, and life span if we want the wave to be free and happy.

“A wave can be recognized by signs—high or low, beginning or ending, beautiful or ugly. But in the world of the water, there are no signs. In the world of relative truth, the wave feels happy as she swells, and she feels sad when she falls. She may think, ‘I am high,’ or ‘I am low,’ and develop a superiority or inferiority complex. But when the wave touches her true nature—which is water—all her complexes will cease, and she will transcend birth and death.” (Thich Nhat Hanh).

A single drop of water has the power to lead him to the place where the water shines. We see this reflected in the projections on the ice as we head into One Summer’s Day—the opening notes, like we saw during the program’s debut outing at GIFT, are accompanied by ripples of water that spread outward, disturbances to the still surface caused by a single drop of water. The droplet becomes ripples, the ripples break apart the otherwise still body of water, and then accumulate to become the unpredictable roiling waves and currents. Then there’s specks of green that begin to shine through the surface too, and the projection ends with him standing in the centre of a powerful whirlpool. And it’s all set in motion by a singular drop of water.

What we see is a massive expanse of blue. It’s what reminded Yuzuru that he’s alive, that he can feel, because he is only a single droplet of water that’s part of a larger, formless mass of water. In this he finds endless comfort after his unanswered prayer. He realizes that his prayer was answered in a different way, because there is endless life and death and life again all around him. It’s here that he finds his prayer answered—it’s here that he finds his god.

The droplet belongs to the vast, unquantifiable stretch of water. But instead of losing himself in its mass, Yuzuru finds his way back to selfhood, just like Haku and Chihiro in the emotional climax of Spirited Away. Chihiro discovers—recovers—Haku’s true identity as the river guardian spirit, in addition to the fact that Haku had saved her as a child when she fell into the rivers. At this revelation, Haku’s dragon scales scatter away into the wind as he transforms back into his human form, along with Chihiro’s tears of joy, and the overwhelming sensation of the scene is nothing short of exuberant as they simultaneously fall into the river and fly up toward the sky. The same way that Haku is able to recover his own lost identity the moment Chihiro calls him by his true name, Yuzuru finds his way back to himself—and discovers that it isn’t so lonesome after all.

The water signifies cleanliness, it signifies a death that cyclically gives way to life, and above all it signifies unconditional belonging and endless transformation—a divinity and a spirituality that is not contained by the conventional structures of deity and devotee,

“... for all is like an ocean, all is flowing and blending; a touch in one place sets up movement at the other end of the earth.” (Fyodor Dostoevsky).

It’s nothing like the “raging stream” that consumed Yuzuru in the first half, violently crashing against him as it threatens to carry the remnants of his selfhood away into oblivion. There’s no travelling against destiny in a narrow river, no sustainable or feasible way of battling your way upstream. But in the vast spread of sea, you are part of a myriad so great that it’s impossible to comprehend through the human mind. The prayer that had gone unanswered in Requiem no longer matters—a single droplet was enough to lead him in the direction of god, to the location where the water shines. Yuzuru is now part of the water itself. Instead of feeling lost and adrift, he finds that there’s immense comfort in it, in being the entirety of the free-flowing ocean.

III. Haru yo Koi, work as prayer

Like a drop of water returning to the ocean, Yuzuru accepts that he is a part of everything. Then, when he acts, he will reach everyone—as he is not separate from, but part of and equal with all existences in heaven and earth.

“Enlightenment, for a wave in the ocean, is the moment the wave realizes it is water. When we realize we are not separate, but a part of the huge ocean of everything, we become enlightened. We realize this through practice, and we remain awake and aware of this through more practice.” (Thich Nhat Hanh).

In layman’s terms:

“[...] we are born alone and meant to die alone and in all our individual experiences on the journey of self-realization we are all alone; but there is also a common factor in that chronology of human experience that binds us all in a sort of universal brotherhood. [We] find redemption not in heaven or some other world, but on the very Earth through common humane experience.” (Amandeep Narang).

With this understanding, Yuzuru becomes his own divinity, his own higher power, his own god. Instead of sending up wishes to a removed higher power, he sees that his artistic practice itself IS his prayer. Finally, in Haru yo Koi, he reaches full on-acceptance for the idea of intentional, thoughtful work as prayer.

“If you work that way and you've got a gift, let's say, and you work, it's like a prayer. So when you go to work, it's praying.” (Martin Scorsese)

When you pray as an artist does, the mundane repetitions you do in your everyday life for the thoughtful, considered practice of that art become your prayer. For a writer, it may be the painstaking practice of slotting one word after the other to commit some complex facet of humanity to the page. For a fine artist, the gestural movements of painting come together to create an indelible image which will strike the heart. For a film director, the toil of endless retakes in the service of a grand story showcasing humane experience. And so on and so forth, for all kinds of artists. All of this, to reach out to their fellow humans and help us feel less alone in our shared, befuddling state of existence.

“The allotted function of art is not, as is often assumed, to put across ideas, to propagate thoughts, to serve as example. The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good. Touched by a masterpiece, a person begins to hear in himself that same call of truth which prompted the artist to his creative act. [...] In those moments we recognize and discover ourselves, the unfathomable depths of our own potential, and the furthest reaches of our emotions. ” (Andrei Tarkovsky).

These repetitive acts of praying are the mark of the artist choosing to stay grounded in their divine, visionary love. And it is through this praying that the artist creates, and thus spreads their divine love to the masses. What is the value of art? If we think of art providing tangible relief, efforts lie. Art will not stop famine or save anyone from physical hardship. And yet the artist gives value to this world still—by making the world bigger and less lonely by creating something true, in which others can find understanding. In the best works of art, do we not feel a connection to the rest of humanity regardless of time or distance?

“Efforts will lie, but will never be in vain." (Yuzuru Hanyu)

For Yuzuru the artist, prayer manifests itself in the effort it takes to convey his vision through skating. Applied to the show itself, we can find it in the repetitive nature of run-throughs, the impetus of his body on the ice, the careful designing of costumes and stories and programs, the collaboration with musicians and directors and graphic artists, etc.

Perhaps his body had understood it before his mind did, this idea of work as prayer. But it’s not until Yuzuru goes through the awakening in the second half, that his mind becomes fully enlightened to it.

And once he awakens, Yuzuru re-prays.

by N (@satokomiyahara) & J (@girlsaint)

I feel like I need to re-read and re-read this again, but so much resonates. Above all, the idea of work as prayer, the idea of honing one’s craft with its endless repetitions in search of something pure that resembles the ritualistic, repetitive nature of prayers, from chants to rosaries. It reminds me of Yuzuru’s practices, the sense of peace that frequently appears on his face as he performs cooldowns….his devotion to practice is often framed as a dogged pursuit of perfection, but maybe perfection isn’t always the right term - maybe it is a pursuit of clarity instead. I can’t help but think of his interviews in (I think) J-Nats 2021, when he spoke about the way skating to his past programs allowed him to find his way home, out of the spiralling doubts and darkness - that, too, feels like a prayer.

The choice of haru yo koi, the program that provides so much healing and catharsis within his last 4 years, feels very aptly positioned then - it indeed represents Yuzuru’s work that is perhaps most unheralded, no glory attached to it, yet like the smallest flowers that bloom in spring, its transformative power to bring hope and to reflect the beauty of being human with all its impermanence is immense.

u r full of endless wisdom